What does contemporary collecting mean?

Contemporary collecting can be defined as collecting objects, materials, and stories from the recent past or present-day events that represent culture in its current form. Many cultural heritage institutions specify that contemporary collecting encompasses “living memory” or objects from the last 50 years.

This type of collecting can fill gaps in existing collections and provides an accurate picture of recent history. Ultimately, it ensures our history is preserved and maintained so people can access and learn from its vast knowledge. The ordinary and everyday are important for contemporary collecting: while something might seem mundane now, it could tell something profound in the future. It’s about preserving real time events that will become important historical references later on.

“Contemporary collecting attempts to rectify past omissions, to give voice to those previously ignored, and to capture a fuller more nuanced record of society whilst material is abundantly available. It seeks to future-proof the museum for as-yet-unknown exhibitions and research.”

Owain Rhys and Zelda Baveystock in Collecting the Contemporary: A Handbook for Social History Museums (2014).

Contemporary collecting can involve partnerships or collaboration from local communities, which not only allow for more creative and engaging outcomes, but they also make it a more diverse and economically viable process.

Deciding how and what to collect

Plan for collection

Creating procedures and processes for contemporary collection can help you fulfil your institution’s central goal and guarantees that you remain focused on the protection of history and cultural heritage. Collection planning is essential to mitigate the risk that your collections become unmanageable or disordered time capsules. Clear boundaries and specifications can be created to determine what things are collected and are not. Resources and storage space is often limited for cultural heritage institutions, so approaching contemporary collecting from a strategic standpoint ensures you do not feel overwhelmed.

Fill the gaps

You can begin contemporary collecting by locating any gaps your collections may have. Complete a top-level review that identifies what your collection has and what it might need more of in relation to the last 50 years. Are there events or themes that are well represented? Or can they benefit from further collecting to bring them up to date? What might be missing from your collections? Create some aims for your contemporary collecting so you can begin with clear parameters detailing what you hope to find.

Mirror contemporary events

Many people believe cultural heritage institutions are no longer simply repositories of bygone history and memory but that they should also mirror contemporary events and invite critical thinking. Institutions, such as museums, can evolve to become public spaces where cultural diversity is celebrated and participation is encouraged by all walks-of-life: your contemporary collecting can help secure this.

Diversity in collecting

With contemporary collecting, people can see themselves represented in your collections: you will be preserving their thoughts, memories, and experiences. Ideas of history and cultural heritage have changed dramatically over time — once themes surrounding colonialism might have been prevalent, exacerbating problematic notions like the “other”. Since the 1980s there has been a push for more inclusive collecting that puts the ordinary and everyday at the forefront and represents a wide range of experiences.

Unique and significant

How can you predict what events and their ephemera will be historically or culturally important in the future? How can you decide what will inspire future historians?

Cultural heritage institutions have to make educated guesses to decide what they should collect and when. A good indicator of whether an object will have historical worth in the future is whether or not it already yields rich insights: what does it communicate about the time it is from? Is it representative of something key within our current society? Does it relate to a crisis or important event? You might want to consider recording and gathering ephemera from current fashion, trends, community initiatives, anniversaries, politics, local news, and significant events.

It is obvious that some events will have great historical importance, like the New Zealand Christchurch Earthquakes, the Australian bush fires, UK Brexit, or the global Covid-19 pandemic. These major events are prime subjects for contemporary collecting, and it can be easy to identify what objects or stories will be relevant. However, make sure you do not forget about the everyday experiences of your community, because they may be just as valuable in the future, divulging important stories relating to our culture and way of life.

Challenges for contemporary collecting

Consider the fragility of items to prioritise their collection

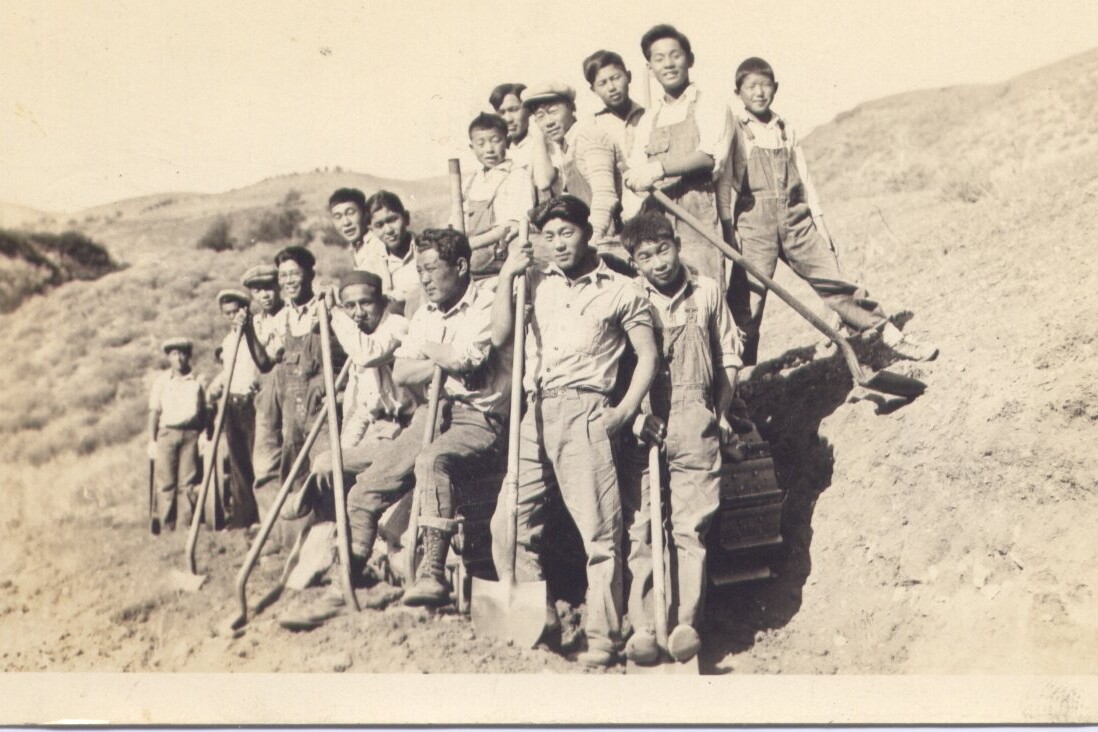

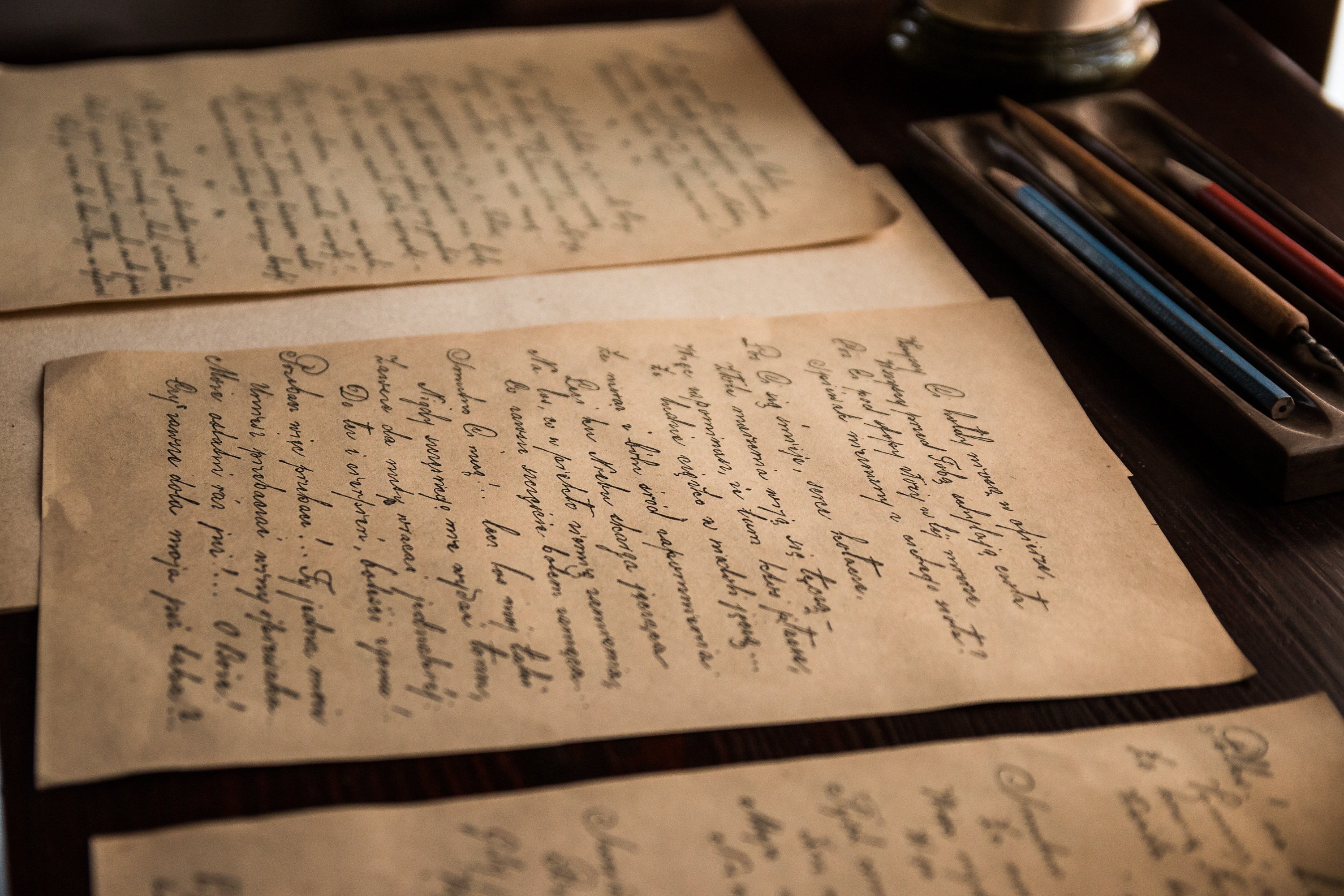

Determine what material will survive without collection and those that will likely be lost without intervention. Larger, heavy objects like furniture will probably survive into the future, but more fragile objects like newspaper clippings, posters, or clothing will probably need to be collected so that they do not deteriorate. Often more ephemeral artefacts will be of great interest to historians, so make sure you consider these carefully when creating a collecting plan. Photographs can also be incredibly valuable to collect: they open a window into the past, allowing the viewer to see what life was like first-hand.

Consider the political, emotional, and social implications

Sometimes material culture can be sensitive; it can affect people emotionally, particularly when artefacts relate to a traumatic event like a disaster. When a cultural heritage institution decides to collect something, they are automatically identifying it as “significant” which could be upsetting to some groups. If an item is extremely controversial, you could seal it in an archival box and clearly label that it contains sensitive material. Always approach contemporary collecting with compassion and respect: this ensures you are operating in an ethical manner. Be open about your motivations for collecting something and consider the various meanings of an object or record.

Evaluate copyright and licensing

Make sure you know the copyright or intellectual property rights of the objects you are hoping to collect. It is important that this is clearly documented once you acquire the material so that people who display or use them in the future are aware of this and understand their responsibilities to ensure it is used appropriately.

People who donate material to your institution should know how their material could be used and what their rights are. Informed consent can be obtained by giving donors information setting out the range of possibilities or situations where their material may be used. You can ask them to fill out a permission form or a donor agreement form to make sure they understand their rights. Try to approach acquiring permission from a flexible standpoint — what may be appropriate for one situation may not be for another.

Diversify your collecting

Try to collect objects that represent various worldviews and experiences, otherwise you could skew how we perceive the situation in the future. Collect from a wide range of people and communities to uphold your institution’s integrity. Unfortunately, it is all too common for museums to disproportionally represent one worldview — frequently catering to those who are middle-class, white, or privately educated. It is important to be aware of this unconscious bias and make an effort to be more inclusive by seeking out alternative sources of information. Cultural heritage institutions should reflect our society as a whole; providing an accurate picture of our society’s diverse interests, ethnicities, and socio-economic backgrounds.

When should you display contemporary collections?

Once you have begun contemporary collecting it can be helpful to determine when you will need to start curating and sorting through the objects you have collected. Some institutions will take the time to create and examine datasets relating the material they have collected before they curate them for an exhibition. Ask questions like: when will we exhibit the material? In a month, a year, or several years? How soon after an event is it appropriate to display objects or stories? How can we preserve objects it in a way that will make sense in the future?

Collecting social media

Social media is ubiquitous to contemporary life, so it can make sense to prioritise its collection. Digital culture, like social media, is often not afforded the same value as more tangible objects but this can be a huge mistake. Memes, hashtags, gifs, and other social media interactions can offer valuable insights about current popular culture and expose people’s thoughts about certain topics like politics, social issues, or community values. Social media encourages and facilitates communication and the exchange of information.

Contemporary collecting of social media exposes a new range of issues relating to copyright and ownership. How can you determine where a meme was originally shared or who created it? How do you obtain permission to display it as part of an exhibition? Cultural heritage institutions may need to revaluate their stance on permission and ownership when dealing with the participatory realm of social media.

Rapid response collecting

Originally coined by the Victoria and Albert Museum in London, rapid response collecting describes the ongoing and immediate collection of objects or stories from breaking news events or global crises. It is a more instant reaction to contemporary collecting: there is a drive to collect as much information as possible while still “in the moment.” It leaves curation and sorting for a later time when there is less urgency. Adopting rapid response collection keeps cultural heritage institutions up-to-date with social and political developments.

How can Recollect facilitate contemporary collecting?

Recollect recognises that communities are an important and plentiful source of historically significant stories and artefacts. A Recollect site can serve as a digital repository to preserve the items and information you are collecting. Recollect also generates online engagement which is key to contemporary collecting because it invites collaboration and opportunities for communities to connect.

After you have decided what kind of history you would like to add to your collections, Recollect can help you capture it in an authentic and collaborative way. You can ask your community to upload stories or images directly to your site, to contribute recollections by commenting directly on individual items, or simply to suggest metadata relating to your current collections through tagging people, places, or transcribing audio.

Objects and ephemera currently residing in your collections can be complemented and supported by contemporary film, photography, and even oral histories. Your community can help you shape your contemporary collecting and add an element of creative flexibility and diversity. However, Recollect is a fully moderated and managed platform, so you can have “peace of mind” that you control what is contributed to your online collections. You can curate and determine what is published to your Recollect site and what material is made available to your communities.

How are museums or cultural heritage institutions responding to Covid-19?

Momentous events change the fabric of our society and it is important to document how and why these changes occurred. We can better understand the effect on our local communities and the ways we could respond to similar situations differently in the future for better outcomes. A large number of cultural heritage institutions are documenting the Covid-19 pandemic: collecting images and stories that detail what life is like during these unprecedented times. Recollect sites from Upper Hutt City Library and the State Library of South Australia are being used to document their community’s response to Covid-19 and record their experiences of lockdown.

Contemporary collecting can allow your institution to:

- Encourage community engagement and collaboration.

- Open up collections to new audiences who may be interested in more contemporary histories.

- Spark partnership opportunities and community crowdsourcing projects.

- Better resonate with your audiences by preserving relevant stories and objects.

- Expand collections to fill any information gaps and make sure they remain current.

- Highlight and celebrate links between the past and present.

Reference and resources

- Atkinson, R. (2020, April 27). New Covid-19 contemporary collecting projects launched. Retrieved from https://www.museumsassociation.org/museums-journal/news/24042020-new-covid-19-contemporary-collecting-projects-launched

- Brenham Heritage Museum. (2017, November 14). Collecting Stuff From Today: Contemporary Collecting. Retrieved from https://www.brenhamheritagemuseum.org/collecting-stuff-today-contemporary-collecting/

- Breynard, S. (2017, May 24). Social Media as Museum Object. Retrieved from https://www.museumnext.com/article/live-social-media-museum-object/

- Dattilo, E. (2020, April 20). Museums Making History: Rapid Response Collecting. Retrieved from https://mchenrycountyhistory.org/museums-making-history%3A-rapid-response-collecting

- Hackett, A. (2017). Trash or Treasure? Te Papa and the collecting on everyday material culture. Retrieved from https://researcharchive.vuw.ac.nz/xmlui/bitstream/handle/10063/6597/thesis_access.pdf?sequence=1

- Heal, S. (2020, April 3). Covid-19: the ethics of contemporary collecting. Retrieved from https://www.museumsassociation.org/ethics/03042020-code-of-ethics-covid-19-contemporary-collecting-statement

- Hopkins, O. (2018, July 20). Museums need to focus less on collecting headlines. Retrieved from https://www.dezeen.com/2018/07/20/museums-rapid-response-collecting-trump-baby-blimp-opinion-owen-hopkins/

- Millard, A. (2017, December 13). Rapid Response Collecting: Social and political change. Retrieved from https://museum-id.com/rapid-response-collecting-social-and-political-change-by-alice-millard/

- Museum Development North West, & Kavanagh, J. (2019). Contemporary Collecting Toolkit. Retrieved from https://museumdevelopmentnorthwest.files.wordpress.com/2019/07/mdnw_contemporarycollectingtoolkit_july2019.pdf

- Museum of New Zealand Te Papa Tongarewa. (n.d.). Collecting childhood: objects and stories from kiwi kids. Retrieved from https://collections.tepapa.govt.nz/topic/8828

- Perry, S., & Band, L. (2020, May 6). Signs of the Times: Archaeologists and Contemporary Collecting During COVID-19. Retrieved from https://www.mola.org.uk/blog/signs-times-archaeologists-and-contemporary-collecting-during-covid-19

- Rees, A. (2018, March 13). What does it meme? When social media becomes part of the museum collection. Retrieved from https://museum-id.com/meme-social-media-becomes-part-museum-collection/

- Rhys, O. (2014). Contemporary Collecting: Theory and Practice (Revised, colour ed.). Edinburgh, United Kingdom: MuseumsEtc.

- Rhys, O., & Baveystock, Z. (2014). Collecting the Contemporary: A Handbook for Social History Museums. Edinburgh, United Kingdom: Museums.

- Smith, R. P. (2020, April 15). How Smithsonian Curators Are Rising to the Challenge of COVID-19. Retrieved from https://www.smithsonianmag.com/smithsonian-institution/how-smithsonian-curators-are-rising-challenge-covid-19-180974638/

- Stephens, C. E. (2014, October 24). Stanley moves in. Retrieved from https://americanhistory.si.edu/blog/2012/11/stanley-moves-in.html